有句經典的話是這樣說的:「你比你生產的數據更沒有價值;因為你會說謊,而數據不會(You are now less valuable than the data you produce)」在這個時代,我們也經常在臉書或各種社交媒體中感受到這種威脅:

明明我才稍微多看了什麼東西幾眼,網路就不斷提供給我相關的廣告和資訊,你會因此產生一種「無所逃於天地之間的被監視感」嗎?看到別人的臉書都是各種美食旅行,會讓你內心不太舒服嗎?

如果會,那這項橫跨 27 個國家,將近 100 萬歐洲公民參與關於廣告、炫耀性消費和幸福的綜合研究或許說中了你的心事,因為該研究認為:「廣告是人類不滿情緒的一大來源」。

■ 廣告無所不在

精確的廣告幫助我們找到適合想要的產品,可以少花一點冤枉錢,但或許大家都能感受到:隨著資訊網路普及和資訊內容的碎片化,如何掌握消費者的目光和注意力已經成為當代顯學。不用說太遠的,你不覺得在臺灣,到處可見的工作職位或是授課講座,全都是在教廣告投放或是數位行銷嗎?

故同時,廣告也帶來另外一層的負面刺激:也就是廣告刺激了我買不起的心理,故大量的廣告有可能提高消費的慾望,但也可能造成了人們的比較和幸福感下降嗎?

本研究的基本論述如下:人具有一種相對主義的偏好,而消費是一種渴望引人注目的舉動。也就是我們在感受到幸福和滿足時,其實是透過「與他人比較量化」而來的結果,而不是自身感受到幸福與滿足;正因為如此才更容易受到廣告的影響。

舉例而言,當你買了一輛新車或是新手機時,在一段時間內你會非常愛護它、把玩它,直到你不小心把手機摔了一道裂痕,或是你的鄰居剛好也買了輛連顏色都和你一樣的新車,而且還剛剛好停在你旁邊時,你的「新車幸福感」會很快被相對剝奪。

廣告相對主義論點認為:我們在決定感到滿意之前會觀看、並比較別人的消費,當我們消費更多(通常是不必要的商品)時,我們就會因為看到別人也消費更多而變得更積極比較,這一過程容易產生快樂,或許有更常見的例子:在臉書上,怎麼當我在旅行時,怎麼彷彿大家也同時都在外國旅行?

這時候,我們旅正在行幸福感會因為精確計算的大數據演算法以及朋友圈的訊息傳播,反而讓我的旅行幸福感大幅降低。人之間相互比較所產生的幸福感、優越感、劣等感,乃至於富裕與貧窮都不具備絕對的基準,而是相對比較下的感受,而當代大數據下精確的資訊推波和精確廣告,反而促使的負面比較情緒的增長(Richins ,1995; Easterlin and Crimmins, 1991; Bagwell and Bernheim, 1996; Sirgy, 1998; Dittmar, 2014; Frey, 2007; Harris, 2009)

但是這種比較下所產生的失落感是否能證明與個人的身心健康有直接影響?過去有一些心理或醫生證實了嫉妒對於人的身體各項指數、健康有所影響(Mujcic and Oswald, 2018)但是大規模的研究則較少直接證據。

■ 關於廣告、炫耀性消費與國家福祉之關係

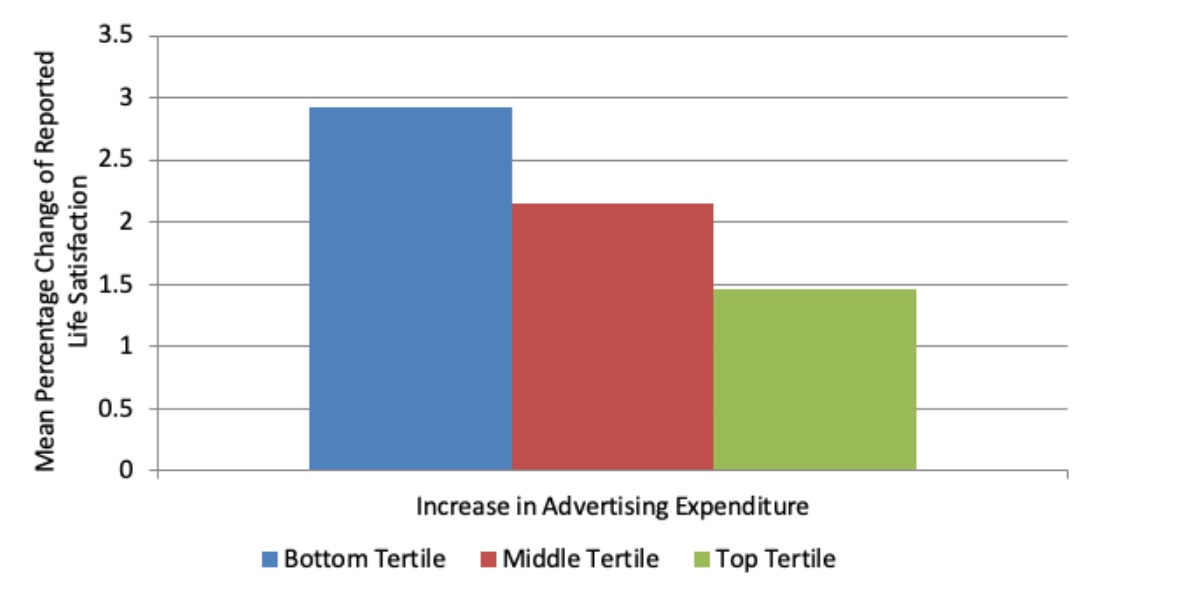

在結論中,本研究中認為廣告傳播與國家福利之間存在負面聯繫的證據(Michel etc.,2019)。從上個世紀 1980 年代到 2011 年,每年針對 27 個國家約九十萬名的歐洲公民進行隨機抽樣實行訪談和調查報告,受訪者報告了他們對於生活滿意度、未來期許以及他們生活的許多其他方面,並紀錄了有關於收看廣告和總支出水平的數據,

The inverse longitudinal relationship between changes in advertising and changes in the life satisfaction of countries, 1980 to 2011

研究儘管炫耀性消費的負面影響已經討論了一個多世紀,但廣告對於個人之間的影響和聯繫還不是很清楚。這個關於歐洲 27 個國家的綜合研究,認為廣告的起伏會隨著國家生活滿意度的下降和上升,廣告的投入與後期福祉之間存在反向關係。簡單來說,如果一個國家在廣告、行銷的支出增長越高,生活的滿意度就會明顯下降。

在根據大約 100 萬人的樣本中,底層包含 1989 年後的捷克共和國、德國、愛沙尼亞、芬蘭、立陶宛、匈牙利、拉脫維亞、波蘭、羅馬尼亞、斯洛伐克,平均變化量為 2.93,中層包含保加利亞、德國西部(1989 年之前)、丹麥、英國、瑞典、斯洛文尼亞、荷蘭、土耳其、西班牙組成,平均變化量為 2.15。上層包括奧地利,比利時,法國,希臘,克羅地亞,愛爾蘭,意大利,挪威,葡萄牙。平均變化量為 1.46。在研究後半,認為廣告所帶來的生活不滿度大約是失業和婚姻破裂的一半到四分之一。

有興趣的請參考下列的相關參考資料。

SOURCE

Andreyeva T, I R Kelly, R Inas, and J L Harris (2011), “Exposure to food advertising on television: Associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity”, Economics and Human Biology 9: 221-313.

Bagwell L S and B D Bernheim (1996), “Veblen effects in a theory of conspicuous consumption”, American Economic Review 86: 349-373.

Borzekowski D L G and T N Robinson (2001), “The 30-second effect: An experiment revealing the impact of television commercials on food preferences of pre-schoolers”, Journal of the American Dietetic Association 101: 42–46.

Buijzen M and P M Valkenburg PM (2003a), “The unintended effects of television advertising: A parent-child survey”, Communication Research 30: 483–503.

Buizjen M and P M Valkenburg PM (2003b), “The effects of television advertising on materialism, parent-child conflict, and unhappiness: A review of research”, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 24: 437-456.

Burroughs J E and A Rindfleisch (2002), “Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective”, Journal of Consumer Research 29: 348-370.

Clark A E (2018), “Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next?”, Review of Income and Wealth 64: 245-269.

Di Tella R, R J MacCulloch, and A J Oswald (2001), “Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness”, American Economic Review 91: 335-341.

Di Tella R, R J MacCulloch, and A J Oswald (2003), “The macroeconomics of happiness”, Review of Economics and Statistics 85: 809-827.

Dittmar H, R Bond, M Hurst M, and T Kassar (2014), “The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107: 879-924.

Easterlin R A (1974), Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence, in: P A David and M W Reder (eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramowitz. Academic Press: 89-125.

Easterlin R A (2003), “Explaining happiness”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 100: 11176-11183.

Easterlin R A and Crimmins E M (1991), “Private materialism, personal self-fulfillment, family life, and public interest”, Public Opinion Quarterly 55: 499-533.

Frey B, C Denesch, and A Stutzer (2007), “Does watching TV makes us happy?”, Journal of Economic Psychology 28: 283–313.

Harris J L, J A Bargh, and K D Brownell (2009), “Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behaviour”, Health Psychology 28: 404–413.

Layard R (2005), Happiness: Lessons from a new science, Penguin.

Michel C, M Sovinsky, E Proto, A J Oswald (forthcoming), “Advertising as a Major Source of Human Dissatisfaction: Cross-National Evidence on One Million Europeans”, to be published in 2019 in a volume in honor of Richard Easterlin.

Opree S J, M Buizjen and E A van Reijmersdal (2016), “The impact of advertising on children’s psychological wellbeing and life satisfaction”, European Journal of Marketing 50: 1975-1992.

Oswald A J (1997), “Happiness and economic performance”, Economic Journal 107: 1815-1831.

Radcliff B (2013), The political economy of human happiness: How voters’ choices determine the quality of life, Cambridge University Press.

Robinson J (1933), Economics of imperfect competition, Macmillan.

Sirgy M J, D J Lee, R Kosenko, H L Meadow, D Rahtz, M Cicic, G Xi Jin, D Yarsuvat, D L Blenkhorn, and N Wright (1998), Does television viewership play a role in the perception of quality of life? Journal of Advertising 27: 125-142.

Sirgy J M, E Gurel-Atay, D Webb, M Cicic, M Husic, A Ekici, A Herrmann, I Hegazy, D-J Lee, and J S Johar (2012), “Linking advertising, materialism, and life satisfaction”, Social Indicators Research 107: 79-101.

Snyder M and K G Debono (1985), “Appeals to image and claims about quality – Understanding the psychology of advertising”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49: 586-597.

Speck S K, A Roy (2008), “The interrelationships between television viewing, values and perceived well-being: A global perspective”, Journal of International Business Studies 39: 1197-1219.

Veblen T (1899), The Theory of the Leisure Class, Macmillan.

Veblen T (1904), The Theory of Business Enterprise, Charles Scribner’s Sons.

https://voxeu.org/article/advertising-major-source-human-dissatisfaction